Introduction

Customer-forward organisations are consistently exploring ways to generate long-term customer loyalty. Customer satisfaction may not be enough to generate customer loyalty because customers may lack interest and incentives to continue their business with any given organisation.[1]

This essay will discuss how a ‘surprise and delight’ strategy contributes to customer experience and the positive effects that such a strategy may have according to Kim and Mattila (2013),[2] as well as any additional pitfalls that it may have and how these can be mitigated. Lastly, this essay will examine how a ‘surprise and delight’ strategy may relate to The CX Academy Framework and its six component elements.[3]

Customer delight can be defined as “‘higher levels’ of satisfaction and/or service quality that may produce exceptional behavioral results, such as greater loyalty.”[4] Delight is an emotional response conducive to customer loyalty and loyalty-driven profit.[5] There are many definitions of customer loyalty with varying elements.[6] However, it can be defined as ‘a positive belief, generated over the course of multiple interactions, in the value that a company and its products or services provide, which leads to continued interactions and purchases over time’.[7]

A ‘surprise and delight’ strategy

A strategy of surprising customers has been found to cause activation or arousal in them and,[8] along with joy, positively impacts customer delight.[9] A ‘surprise and delight’ strategy may offer sustained results if efforts are designed thoughtfully and for the right context.[10] It is important to note that not all contexts are appropriate. In basic services provided by public utilities, a strategy of ‘surprise’ may be unnecessary.[11] In some contexts, it may even be inappropriate. However, in some service encounters, customers often desire surprising outcomes,[12] and ‘surprise’ rewards have been found to enhance customer delight compared to offering discounts.[13]

Understanding potential pitfalls when designing a ‘surprise and delight strategy’ is essential. Such strategies may raise customer expectations, thus increasing the difficulty of meeting (never mind exceeding) those expectations in the future. This risk can be mitigated by providing customers with an explanation and reasons for the surprise, thus effectively managing their expectations.[14] Providing explanations may also enhance customer delight and strengthen the relationship between organisations and their customers.[15] Another strategy that can be followed to prevent customers from becoming habituated to receiving surprises is to offer these infrequently and randomly.[16]

The CX Academy Framework: We’ve a real bond

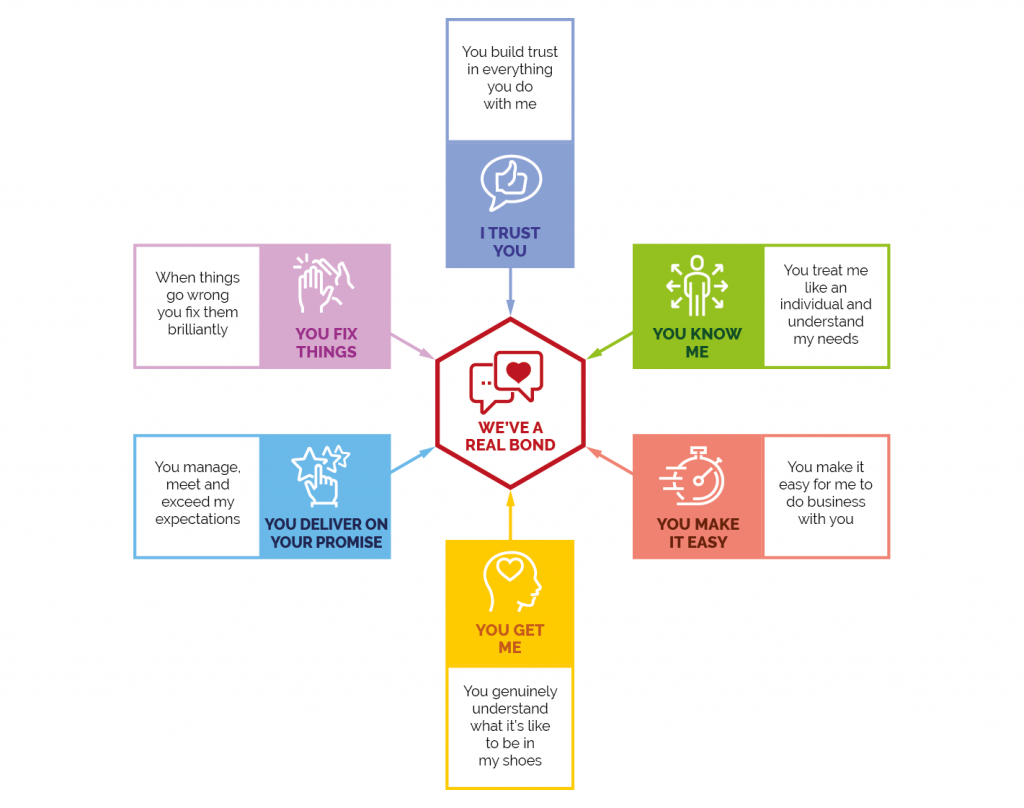

To build loyalty, companies may elicit emotional responses from customers, such as seeking to delight customers by providing them with pleasant surprises. The CX Academy Framework, through its six emotional drivers, serves as a practical framework through which organisations can design context-appropriate ‘surprise and delight’ strategies that result in customer loyalty and a ‘real bond’ between brands and their customers.

I trust you

The first emotional driver is ‘I trust you’. Customer trust is customers’ confidence in a company’s commitment to meeting their expectations and acting with their best interests in mind.[17] This element is fundamental in creating real bonds with customers. For this reason, a ‘surprise and delight’ strategy should not be concerned with meeting or exceeding customer expectations;[18] it must seek to design unexpected experiences while cultivating a relationship with customers where the fundamental pillars are never compromised. Organisations must ensure that customers build realistic expectations[19] and must be very careful when introducing elements of surprise as these may lead to entitlements, ultimately affecting customers’ perceptions of reliability and negatively impacting trust.

You know me

The second emotional driver is ‘You know me’, which refers to treating customers like individuals, like human beings. By leveraging customer data and identifying customer needs, organisations can design experiences that address those needs.[20] By getting to know their customers and being mindful of the business context, organisations can implement ‘surprise’ strategies that delight customers at an individual level in key customer journey points. One approach organisations may take is training employees to identify individual customer needs and empower them to respond with simple, random, surprising outcomes and acts of kindness that may result in customer gratitude.[21]

You make it easy

The third driver in the framework is ‘You make it easy’, which refers to reducing friction and barriers in the customer journey. As we have mentioned, a strategy of ‘surprise and delight’ without providing appropriate explanations may cause friction or even negative feelings, such as guilt.[22] In order to delight customers, organisations must design ‘surprise’ strategies that provide appropriate explanations. Ultimately, organisations must not lose focus on reducing friction and must design processes and procedures that foster gratitude amongst their customers, even if elements of surprise are not introduced.[23]

You get me

The next emotional driver is ‘You get me’, which refers to understanding customers’ circumstances and showing empathy in all interactions. Any ‘surprise and delight’ strategy must be designed along an empathic execution. Organisations must hire emotionally intelligent employees and foster empathy within the existing workforce to achieve a ‘gratitude-driven’ delight that compliments ‘surprise-driven’ delight.[24]

You deliver on your promise

The fifth emotional driver is ‘You deliver on your promise’, which refers to managing and meeting customer expectations. Companies can achieve customer experience excellence and delight customers by delivering on their promises.[25] A strategy of ‘surprise and delight’ may have the unintended consequence of raising customer expectations,[26] and it may be required to deliver considerably above expectations,[27] thus making it harder and more expensive to delight customers in the long term. Any successful ‘surprise and delight’ strategy must consider long-term effects on the customer promise and use proactive communication to manage expectations effectively.[28]

You fix things

The last driver is ‘You fix things’. It can be expected that, occasionally, things may go wrong. However, how quickly and effectively organisations respond matters. Any ‘surprise’ strategy an organisation deploys is doomed to fail if the organisation is not reactive or responsive when problems arise. It is not enough to fix things: ‘surprise and delight’ strategies must look at closing the loop with customers and communicate improvements and tactical and strategical changes made as a result. This action resets customer expectations and eliminates any potential negative surprises brought about by the changes introduced.[29]

Conclusion

Modern consumption cannot be limited to satisfying customers: simply delivering basic needs may indeed cause dissatisfaction.[30] Organisations may design strategies that delight customers and build loyalty through elements of surprise while understanding the potential pitfalls of such strategies and planning accordingly. In the CX Framework, organisations have a valuable tool to design ‘surprise and delight’ strategies that elicit the desired emotional responses in customers.

References

[1] B. Schneider and D.E. Bowen, ‘Understanding customer delight and outrage’, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 41 No. 1 (1999), 35–45; X. Wang, ‘The effect of unrelated supporting service quality on consumer delight, satisfaction, and repurchase intentions’, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 14 No. 2 (2011), 149–163, cited in Kim and Mattila, 2013, p. 361.

[2] Min Kim and Anna Mattila, ‘Does a Surprise Strategy Need Words? The Effect of Explanations for a Surprise Strategy on Customer Delight and Expectations’, Journal of Services Marketing, 27 (2013).

[3] The CX Academy, ‘The CX Framework’, The CX Academy.

[4] Howard Schlossberg, “Satisfying Customers is a Minimum; You Really Have to ‘Delight’ Them”, Marketing News, 24 (May 28, 1990), 10–11, cited in Richard L. Oliver, Roland T. Rust, and Sajeev Varki, ‘Customer Delight: Foundations, Findings, and Managerial Insight’, Journal of Retailing, 73.3 (1997), p. 312.

[5] Oliver et al, 1997, p. 321.

[6] Bob Thompson, The Loyalty Connection: Measure What Matters and Create Customer Advocates (2007), cited in Dr Muhammad Tariq Khan, ‘Customers Loyalty: Concept & Definition (A Review)’, 5 (2013), p. 169.

[7] Oracle Corporation, ‘Ensuring Customer Loyalty: Designing Next-Generation Loyalty Program’, An Oracle White Paper (2005), cited in Khan, 2013, p. 169.

[8] William R. Charlesworth, ‘The Role of Surprise in Cognitive Development’, Studies in Cognitive Development, ed. by David Elkind and John H. Flavell (New York: Oxford University Press, 1969), pp. 257–314, cited in Oliver et al, 1997, p. 317.

[9] Joan Ball and Donald C. Barnes, ‘Delight and the Grateful Customer: Beyond Joy and Surprise’, Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27.1 (2017), p. 260.

[10] R.T. Rust and R.L. Oliver, ‘Should we delight the customer?’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 28 No. 1 (2000), pp. 86–94, cited in Ball and Barnes, 2017, p. 261.

[11] Oliver et al, 1997, p. 329.

[12] E.J. Arnould and L.L. Price, ‘River magic: extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 24–45, cited in Ball and Barnes, 2017, p. 255.

[13] L. Wu, A.S. Mattila and L. Hanks, ‘Investigating the impact of surprise rewards on consumption responses’, Investigating the impact of surprise rewards on consumption responses, Vol. 50, pp. 27–35, cited in Ball and Barnes, 2017, p. 257.

[14] Kim and Mattila, 2013, p. 366.

[15] Ibid., p. 366

[16] Ibid., p. 366

[17] Court Bishop, ‘How to Build Customer Trust: 4 Things to Start Doing Today’, Zendesk UK, 2022.

[18] Tim Tyler, ‘Does “Surprise & Delight” Have a Place in Customer Loyalty?’, On Point: Perspectives from Ellipsis, 5 (2016).

[19] R.W. Coye, ‘Managing customer expectations in the service encounter’, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 54–71, cited in Min and Mattila, 2013, p.363.

[20] My View Research, ‘Why Treating Customers As Individuals Is Important’, My View Research, 2022.

[21] Ball and Barnes, 2017, p. 264.

[22] Kim and Mattila, 2013, p. 366.

[23] Ball and Barnes, 2017, p. 262.

[24] Ball and Barnes, 2017, pp. 262–264.

[25] R. Johnston, ‘Towards a better understanding of service excellence’, Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, Vol. 14 Nos 2/3, pp. 129–133, cited in Ball and Barnes, 2017, pp. 251.

[26] Kim and Mattila, 2013, p. 366.

[27] Richard L. Oliver, ‘Effect of Expectation and Disconfirmation on Postexposure Product Evaluations: An Alternative Interpretation’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 62 (August 1977), pp. 180–186, cited in Oliver et al, 1997, p. 321.

[28] Kim and Mattila, 2013, p. 366.

[29] Annette Franz, Closing the Loop to Surprise, Delight, and Retain Customers (NICE, 2022), p. 8.

[30] Richard L. Oliver, ‘Processing of the Satisfaction Response in Consumption: A Suggested Framework and Research Propositions’, Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 2, pp. 1–16, cited in Oliver et al, 1997, p. 314.